just the activity by which poets achieve their fame. A vast amount of literary criticism can be dismissed outright on this basis.

Consider pop music, by contrast. The technique and technology of pop make the pop song available as a vehicle to the ambitious young man or woman who wants to become famous. It is like any other tool. You buy it and use it to some end. There is no guarantee that you'll succeed, of course; the point is merely that the song's only value lies in the end it achieves for the would-be star. It has no aesthetic value, only an instrumental one.* A poem, however, lacks the institutional immediacy to present itself to the public as a temporary means to the end of the poet's destiny. The poem is itself the poet's destiny. It is permanent or it is nothing.

The surrealists wanted to put poetry (art in general) at the service of the revolution. They were half kidding, of course. The impossibility of revolution does not render artistic activity meaningless. It is meaning.

The situationists reversed it: they wanted to put the revolution at the service of poetry. Again, the impossibility of revolution does not undermine the possibility of poetry.

___________

*Before you defend one or another gem of a pop song as "art" in its own right, keep in mind that I'm thinking of pure forms here. Some songs accomplish, within the technical and institutional framework of pop an "aesthetic" quality that is often admirable. (I can enjoy any number of popular songs.) But in these cases poetry (art) struggles against "the industry" (commerce). And the artist is, damn blast yer intellex, complicit in the compromise. You cannot record a popular song for purely artistic reasons. But you can (and must) write a poem for such reasons.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Poetry is not

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Institutions and Media

Some things are experienced immediately. We know right away what we're looking at, what we're dealing with. I'm not talking about moments of instant recognition, about which we could be mistaken. I'm talking about the comfortable way in which we know our way home through the park. The certainty that this is the park, which would be true even in a dream (a dream about the park). I'm talking about what it is like to be at home in the ordinary way.

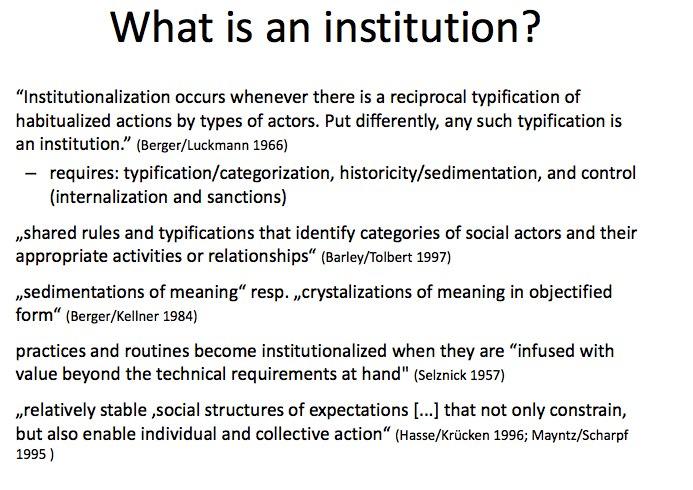

I thought about this when Liam Stanley tweeted the following slide to explain "what, exactly, an institution is in political and social science":

These are all perfectly good definitions. But I've always thought we should define institutions in contrast to mediated forms of experience. If you have to ask what an action means, it is not "typical", i.e., it is not institutionalized.

I think specifically of Kant's definition of intuition as a model. Intuition is that through which knowledge of things is given to us immediately. The "that through which" is important because it actually suggests mediation (going through something). So intuition is the medium of immediate knowledge, almost a contradiction in terms.

But then, immediacy is probably an essentially paradoxical notion.

Anyway, institution is that through which the power of people is taken from them immediately. Or the way in which people are immediately taken with experience. Institution is the immediacy of people in experience. (What one definition refers to as the identification of "categories of social actors".) Institution is the immediacy of social experience.

Likewise, intuition is the immediacy of material experience. We experience the world as a collection of things because of intuition. We experience history as a collective of people because of institution.

_________

Update (02-10-2016): Reading this just now it occurred to me that intuition/institution is that through which knowledge/power is distributed in experience immediately. It is the immediacy of sense and motive in experience. That is, institutions don't just take power from people. It is also the medium in which they, immediately, have certain powers. Likewise, intuitions don't just reveal things immediately in any give situation, they also conceal things.

Monday, January 21, 2013

Mayhew's Duende, and Mine

Last night I left a somewhat unhinged comment on Jonathan's post about the duende. This post is just a slightly cleaned up version of that.

I was struck by Jonathan's description of me as a "Danish reader". I don't think there's anything very Danish about my reading of Apocryphal Lorca, and I've never really liked the idea of national literatures. (Pound says that we should no more speak of "American literature" than we should speak of "American chemistry".) In fact, much of the "apocrypha", the kitsch, surrounding the duende derives from tying it essentially to Andalusia. Still, there is of course a way to understand the duende by way of the socratic daimon, which inspired, if you will, much of Kierkegaard's work. In particular, we can distinguish between the "genius" and the "apostle". And we can note that too many readings of both Lorca and Heidegger do not proceed from the reader's own particular genius, but the desire to be an apostle.

Jonathan writes that the duende "is a name for Lorca’s own exceptional poetics, universalizable, in principle, but also irreducibly his own." I think that exactly captures the nature of the interpretative problem, and the problem of translation. He goes on: "In Apocryphal Lorca I suggested the duende—an untranslatable term—was at the same time a master trope for translation itself." Yes, but he also questioned its untranslatability, and suggested (at least to me) that its misreading, and reduction to kitsch, is a function, precisely, of the insistence of translators and followers not to find an equivalent notion in their own language. The whole point of the duende (if we take it "as master trope for translation itself") is that you must appropriate the translated work. The duende is not about Lorca or Spain. It is about you, dear reader.

Kierkegaard says somewhere that if you have to ask how and when sin came into the world, you haven't understood the question. It's sort of like that. "It took eighteen centuries of Christendom," writes Norman Mailer, "before Kierkegaard could come back alive with the knowledge that ... the characteristic way modern man found knowledge of his soul [was] ... by the act of perceiving that he was most certainly losing it." (From the preface to Deaths for the Ladies, reprinted in Existential Errands.) That is, we learn about existence for ourselves, because existence simply is the mystery of self in the world.

The duende is universal and therefore translatable into the name of the ineffable breath of genius in all languages and traditions (daimon, muse, genii, what have you). The idea of Mayhew's duende is jarring (a much needed jolt) for the same reason that, say, Basbøll's Dasein would be jarring. We think these concepts, if they mean anything at all, can only mean what Lorca and Heidegger meant by them. But that misses what Heidegger calls the "in each case mine". Or as Pound said: metaphysics is that about which we can only know what we find out for ourselves. This, I guess, is "what Lorca knew".

By invoking his own duende, or Dasein for that matter, Jonathan is merely (and rightly) insisting on the universal (primordial) meaning of the term. We can go further (via Saint Teresa, perhaps): when Jesus said he was God's son he didn't mean that he, alone, was God's son, he meant we all are. The kitsch of Christianity, then, comes from granting this claim to only one man, who "walked the earth", etc. It was an attempt to stave off a general emancipation with talk of a miracle, an exception. The good news, meanwhile, was meant to be universal. And that was why Kierkegaard ultimately could not call himself a "Christian".

I'm no expert on Lorca's duende. (Nor, for that matter, on Heidegger's Dasein.) But the issue here is what kind of "expertise" is required. Mayhew's approach teaches us (or at least me) to think outside the frame of Spanish, and indeed Lorquian, "exceptionalism" (a frame within which I'm in any case unqualified to think) and try instead to understand, in my own case, "the subtle link that joins the five senses to the living flesh". Likewise, we cannot continue to think of an expert on Dasein as necessarily an apostle of Heidegger. We must, finally, find our own genius.

Saturday, January 19, 2013

Image and Meaning

I feel like I'm on the verge or cusp of an insight.

I've been reading a book by Richard Biernacki called Reinventing Evidence, which draws attention to the puzzling status of "the fact of meaning" in the social sciences. Texts and practices are meaningful and the social sciences (especially ethnography) tells us what they mean—what they mean.

They try to describe human activities as underpinned by (the) facts (of their meaning) to be discovered. And this raises the question of method. The social sciences provide us with a "theory of meaning" for social phenomena, a science of their interpretation. So they must have a "method", which gives them access to the "facts".

The humanities, I sometimes argue, don't have theory and method. They have style.

So we have a choice. We can engage stylishly with our culture or we can undertake to know the facts of social life.

The second option forces us to search, not just for "the meaning of life", but for its particular meanings (pl.). The first, by contrast, and which I favor, requires imagination. It says, not that there are meanings that must be brought out from under the phenomenal flux of experience by means of a method, but rather, and trivially, that there are images, that we imagine things, and, somewhat less trivially, that who we are is shaped by this imagery.

On this view, there is no truth about social life until we understand it.

Like I say, I'm only just now leaning into this insight.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Truths and Rights

I normally say that the pangrammatical supplement of "truth" is "justice". This has much to recommend it, but also one clear defect that I've noted before: there are "truths" in the world, but not corresponding "justices".

I just discovered a way to resolve this problem that might be more elegant than I previously suggested. Can we not distinguish simply between "truth" and "rightness" (i.e., justice). Our beliefs about the world are true and false, while our desires about history are right and wrong.

This also lets us posit truths and rights, and I mean "rights" in the ordinary sense. A right is just an individual just-ness. Our experience, then, is subtended by truths and rights.

Now, the truths are known to us or not. While the rights are mastered by us or not.

(Note that social progress since, say, the Enlightenment has consisted in the increasing mastery of the rights that, we increasingly recognized, we already had.)

One big issue is whether all grounding of actions depends on rights. Are some "abilities" not grounded in "skills"? This is where moral and practical "rightness" intersect. There are right and wrong ways to do things, but there is no simple way to distinguish the social license we have for action from physical ability we have to do it.

We have a "right" to do something, or not. We are able to do it or not.

"You're doing it wrong!"

"What you did was wrong!"

Both of these expressions depend on the experience of an action having "rightness". When we propose "inalienable human rights" or suchlike, are we not just saying that, just as our experience gives us access to truths, it affords us rights?

Error

(I'm not claiming that these platitudes are profound. I'm just noting them down.)

When science errs

it errs against wisdom.

When politics errs,

it errs against love.

Without a viable process

of correction, we'll have

a witless academy and

a loveless polity.

Saturday, January 12, 2013

Love and Wisdom

Philosophy is the love of wisdom,

poetry the wisdom of love.

Wisdom is to know what knowledge is.

Love is to master who power becomes.

Knowledge of knowledge, power of power.

Self-knowledge. Self-mastery.

Wisdom. Love.

Philosophy is an inquiry into knowledge

for the love of wisdom.

Poetry is the governance of power

in the wisdom of love.

Of course, in the world,

there will be knowledge without self-knowledge,

and throughout history,

there will be power without self-mastery.

But there will always also be philosophers

and poets, not to mention wisdom and love.

There will be sages and lovers, too.

Wednesday, January 09, 2013

Tolkien on Technology as the Actualization of Desire

"The ultimate aim of the Elves is art and not power."

Tuesday, January 08, 2013

Obedience, Ideality and Institution

"him who disobeyes/ Mee disobeyes"

Milton

Institutions are normally studied as part of "social reality" and should, indeed, be approached as constitutive of that "reality". It is in our institutions that power is experienced immediately; they are that through which subjects of power are immediately taken with stuff. (Intuition, we will recall, is that through which objects of knowledge are immediately given to us.)

But, as I've suggested before, the idea that social life is "real" is an illusion. Society is not an objective reality; it's a subjective ideality. It is not independent of the material reality that is given to us through intuition, to be sure. But society is simply not real.

We understand the material reality. We obey the social ideality. We should not try to understand "the social". We should learn to obey it.

(Kafka would back me up on this.)

This is why I think poetry is so important. It is as important to politics as philosophy is to science. It is the art of imagining the ideality, just as philosophy is the art of imagining the reality. After all, it's one thing to know what is real; it is quite another to imagine it. In imagination we become aware of the possibilities within the real and the necessities within the ideal. That's why the pangrammatical supplement of "understanding reality" is "obeying ideality". The ideal is simply not something one understands. Or rather, to understand an ideal is simply to obey. There's nothing more to see. Likewise, to "obey reality" is, simply, to understand. That's all it's asking you to do.

Institutions, I will agree with you, are in a lousy state these days. (There's something rotten in the State, as ever.) But we break our hearts trying to understand them. We have only our obedience to work with.

This does not mean that we should do as we are told. Institutions do not "tell us what to do". They determine the immediate rightness of actions. And there are always greater and lesser institutions. Civil disobedience, we must remember, is based on the idea that an act of dissent obeys a higher law.

Monday, January 07, 2013

Imagination and Population

"Though shalt not sit with statisticians." (W. H. Auden)

A stray thought:

When statisticians like Andrew Gelman and Nate Silver write about politics we consider it the most natural thing in the world. After all, they know about populations, i.e., "the people". But when poets like Ezra Pound or Peter Dale Scott write about politics, we're just as likely to dismiss them as cranks. After all, they are only experts of the imagination.

The comparison isn't perfect. Pound is long dead. Scott is 84 years old this week. Gelman and Silver are much younger men. But is there a poet their age today that is writing seriously about politics (I don't mean that they might be writing political poetry), and being taken as seriously as a statistician?

None comes to mind as I write this. But it's one of those questions that you put out there and then someone immediately gives you two or three names that makes everything okay again.

I don't begrudge the statisticians their fame, by the way. But I am saddened by the irrelevance of imagination in political life. The status and function of poetry is a symptom of this.

Thursday, January 03, 2013

Emotion and Society

"...the greatest difficulty, aside from knowing truly what you really felt, rather than what you were supposed to feel, and had been taught to feel..." (Hemingway)

Emotions are to poetry what concepts are to philosophy. Concepts bring precision to theories (the precision of our theories depends on our concepts) and emotions, likewise, bring precision to practices.

That is, emotions are entirely practical entities. They are the "units" of practical mastery. They constitute the texture of our precision in action. They allow us to pass immediately from feeling something in an encounter to acting appropriately.

When I speak of the "appropriate" action, I don't simply mean doing something that is "acceptable" in a social situation. Many of our emotions do have the virtue of such respectability, but not all. Our ability to deal socially with grief, for example, is conditional on the emotions we have available to us to manage in situations where the feeling of loss is present. The mourner and the friend, both, have to draw on their emotional resources to act appropriately. As does the mere acquaintance and the complete stranger when addressing the bereaved.

Everyone feels something when they are around others. Emotions convert those feelings into workable behavior. In some cases, we lack the necessary emotions. The results are familiar.

Some feelings, however, actually require socially inappropriate behavior, and here we require especially precise emotions, which will support very intense experiences.

In any case, our emotional apparatus conditions how feelings are experienced immediately; perhaps more precisely, they make actions immediately meaningful. (Just as a concepts make perceptions immediately meaningful.) Some behavior is not immediately meaningful, and that's simply because we lack the emotions required to attribute a motive to them. (In the case of concepts the problem here is the attribution of sense, not motive.)

The arts keep our emotions working properly, keep them precise. Poetry in particular is the art of refining our emotions in order to keep our experience of social life precise, i.e., intense. The marginalization of poetry (it has been crowded out by sociology and psychology) tells us something important, and distressing, about our culture.

We no longer approach our social relationships through our emotional lives. Most of our actual feelings have become pathologies, or have been outright criminalized. (As Glenn Greenwald has pointed out, the state now wants to control how we express our feelings of, say, hatred.) We have a narrow emotional range. A small set of scientifically constructed emotions. Here "science" does not connote precision; our feelings have been construed as brute "facts" to be expressed in a series of familiar, caricatured gestures. We have become incapable of nuance.

Wednesday, January 02, 2013

Price and Image

Sometimes it distresses me how old a post at this blog is. That it was over three years ago that I suggested that "some arch bank" put usury between our selves and our crafts, and so little has come of that insight is hard to bear. The fact that Ezra Pound has been "on the case" for years is little consolation (see also, and also).

It occurs to me what has really happened is that the price of a thing has displaced our image of it in our assessment of its value. Thus, it no longer matters very much what a thing looks like or what we imagine we can do with it. What matters is what it will cost, and how it will depreciate. Will it gain or lose in monetary value? Not: how will it age? Craftsmanship now has only an incidental relation to the problem. There are no houses of good stone.